In Graz and Paris

Matej Povse/Getty Images

Matej Povse/Getty ImagesTwo shocking attacks within two hours of each other, in France and Austria, have left parents and governments reeling and at a loss how to protect school students from random, deadly violence.

At about 08:15 on Tuesday, a 14-year-old boy from an ordinary family in Nogent, eastern France, drew out a kitchen knife during a school bag check and fatally stabbed a school assistant.

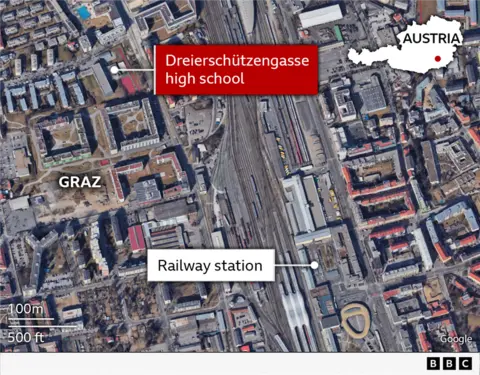

Not long afterwards in south-east Austria, a 21-year-old who had dropped out of school three years earlier, walked into Dreierschützengasse high school in Graz at 09:43, and shot dead nine students and a teacher with a Glock 19 handgun and a sawn-off shotgun.

In both countries there is a demand for solutions and for a greater focus on young people who resort to such violence.

Austria has never seen a school attack on this scale, but the French stabbing took place during a government programme aimed at tackling the growth in knife crime.

Austrians ask about gun laws and a failed system

The Graz shooter, named by Austrian media as Arthur A, has been described by police as a very introverted person, who had retreated to the virtual world.

His “great passion” was online first-person shooter games, and he had social contacts with other gamers over the internet, according to Michael Lohnegger, the criminal investigation chief in Styria, the state where it happened.

A former student at the Dreierschützengasse school, Arthur A had failed to complete his studies.

Arriving at the school, he put on a headset and shooting glasses, before going on a deadly seven-minute shooting spree. He then killed himself in a school bathroom.

He owned the two guns legally, had passed a psychological test to own a licence and had several sessions of weapons training earlier this year at a Graz shooting club.

This has sparked a big debate in Austria about whether its gun laws need to be tightened – and about the level of care available for troubled young people.

It has emerged that the shooter was rejected from the country’s compulsory military service in July 2021.

Defence ministry spokesman Michael Bauer told the BBC that Arthur A was found to be “psychologically unfit” for service after he underwent tests. But he said Austria’s legal system prevented the army from passing on the results of such tests.

There are now calls for that law to be changed.

Alex, the mother of a 17-year-old boy who survived the shooting, told the BBC that more should have been done to prevent people like Arthur A from dropping out of school in the first place.

“We know… that when people shoot each other like this, it’s mostly when they feel alone and drop out and be outside. And we don’t know how to get them back in, into society, into the groups, into their peer groups,” she said.

“We, as grown-ups, have got the responsibility for that, and we have to take it now.”

President Alexander Van der Bellen raised the possibility of tightening Austria’s gun laws, on a visit to Graz after the attack: “If we come to the conclusion that Austria’s gun laws need to be changed to ensure greater safety, then we will do so.”

Austria has one of the most heavily armed civilian populations in Europe, with an estimated 30 firearms per 100 people.

Although there have been school shootings here before, they have been far smaller and involved far fewer casualties.

The mayor of Graz, Elke Kahr, believes no private person should be able to have weapons at all. “Weapons licences are issued too quickly,” she told Austria’s ORF TV. “Only the police should carry weapons, not private individuals.”

French focus on mental health as well as security

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE VERHAEGEN/AFP

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE VERHAEGEN/AFPArmed gendarmes were present at the entrance to the Françoise Dolto middle school in Nogent, 100km (62 miles) east of Paris, when a teenager pulled out a 20cm kitchen knife and repeatedly stabbed Mélanie G, who was 31 and had a four-year-old son.

The boy accused of carrying out the murder told police that he had been reprimanded on Friday by another school assistant for kissing his girlfriend.

As a result he had a grudge against school assistants in general, and apparently had made up his mind to kill one. Schools were closed on Monday for a bank holiday, and Tuesday was his first day back.

The state prosecutor’s initial assessment was that the boy, called Quentin, came from a normal functioning family, and had no criminal or mental health record.

However, the child also appeared detached and emotionless. Adept at violent video games, he showed a “fascination with death” and an “absence of reference-points relating to the value of human life”.

The Nogent attack does not fit the template of anti-social youth crime or gang violence seen in France until now.

Nor is there any suggestion of indoctrination over social media.

According to the prosecutor, the boy did little of that. He had been violent on two occasions against fellow pupils, and was suspended for a day each time.

There is no family breakdown or deprivation and school officials described him as “sociable, a pretty good student, well-integrated into the life of the establishment”.

This year he had even been named the class “ambassador” on bullying.

For all the calls for greater security at schools, this crime took place literally under the noses of armed gendarmes. As Interior Minister Bruno Retailleau put it, some crimes will happen no matter how many police you deploy.

For more information on the boy’s state of mind, we must wait for the full psychologist’s report, and it may well be that there were signs missed, or there are family details we do not yet know about.

On the face of it, he is perhaps more a middle-class loner, and his apparent normality suggests a crime triggered by internalised mental processes, rather than by peer-driven association or emulation.

AFP

AFPThat is what strikes the chord in France. If an ordinary boy can turn out like this from watching too many violent videos, then who is next?

Significantly, the French government had only just approved showing the British Netflix series Adolescence as an aid in schools.

There are differences, of course.

The boy arrested for the killing of a teenage girl in the TV series yields to evil “toxic male” influences on social media – but there is the same question of teenagers being made vulnerable by isolation online.

Across the political spectrum, there are calls for action but little agreement on what should be the priority, nor hope that anything can make much difference.

Before the killing, President Emmanuel Macron had angered the right by saying they were too obsessed with crime, and not sufficiently interested in other issues like the environment.

The Nogent attack put him on the back foot, and he has repeated his pledge to ban social media to under 15-year-olds.

But there are two difficulties. One is the practicality of the measure, which in theory is being dealt with by the EU but is succumbing to endless procrastination.

The other is that, according to the prosecutor, the boy was not especially interested in social media. It was violent video games that were his thing.

Prime Minister François Bayrou has said that sales of knives to under-15s will be banned. But the boy took his from home.

Bayrou says airport-style metal-detectors should be tested at schools, but most heads are opposed.

The populist right wants tougher sentences for teenagers carrying knives, and the exclusion of disruptive pupils from regular classes.

But the boy in Nogent was not a problem child.

About the only measure everyone says is needed is more provision of school doctors, nurses and psychologists in order to detect early signs of pupils going off the rails.

That of course will require a lot of money, which is another thing France does not have a lot of.