Ahmad Dwikat, a Palestinian worker, inspects bars of soap stacked to dry before packing them at a soap factory in the West Bank city of Nablus, on March 1.

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

NABLUS, West Bank — As the sun starts to come up over the old city of Nablus, workers light a giant blaze of a furnace at the Touqan soap factory right off the main square. The blasting flames start to slowly heat a giant vat holding hundreds of gallons of goopy, waxy sludge above. It’s a morning ritual that’s been happening at the factory for more than 150 years.

Musa Assakhal scrapes a metal spatula through the mixture — a combination of virgin olive oil, water and lye — checking the consistency. He flips a switch and a big metal blade starts slowly rotating, gently sloshing the thick liquid onto the surrounding surfaces as it mixes. It’s been boiling on and off for several days.

“I’m waiting for it to boil,” he says. “Once it boils, I’ll know whether it’s ready or not.”

Assakhal has been doing this job for most of his life. His father had the job before him. He used to sometimes come and help when he was a child.

“This job gives me great joy, to be able to do something the way my ancestors did it,” he says, smiling.

The Palestinian city of Nablus has been known for its olive oil soap for centuries, the tradition of making it passed down from generation to generation. In December, the tradition was added to the list of UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, after Palestinian representatives nominated it.

A worker stacks soap bars at the Touqan soap factory in Nablus, West Bank, on March 1.

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

While many families make it in their homes, Touqan, opened in 1872, is one of the oldest factories still in operation. But workers at the factory say that business has slowed, as competition from global brands has increased, but also as the Israeli military occupation of the West Bank has put more and more impediments on owning and operating a business. In recent years, they’ve had to cut staff, and production has decreased by about a third.

In January, Israel launched a new and destructive military operation in the northern part of the West Bank, which it says is for counterterrorism. The operation has displaced tens of thousands of Palestinians from their homes, with forces destroying hundreds of residential buildings, according to the Israeli military, saying the destruction was an “operational necessity.” It has also made the neighborhoods it has focused on unlivable, according to the United Nations, ripping up streets and necessary infrastructure.

The military activity has slowly spread south. On March 21, the Israeli military announced it had begun operating in Nablus, conducting near daily raids in the city.

“We’re living now through the worst military obstacles on the roads leading to where our soap needs to reach our customers,” says Nael Qubbaj, the manager of manufacturing at the factory for the past 30 years.

He says the roadblocks, checkpoints and raids that are part of the Israeli military occupation over the past decades have made it increasingly difficult for the factory to operate. Now, the stepped-up military activity has made it worse. Sometimes workers can’t get to work, or soap shipments can’t get delivered.

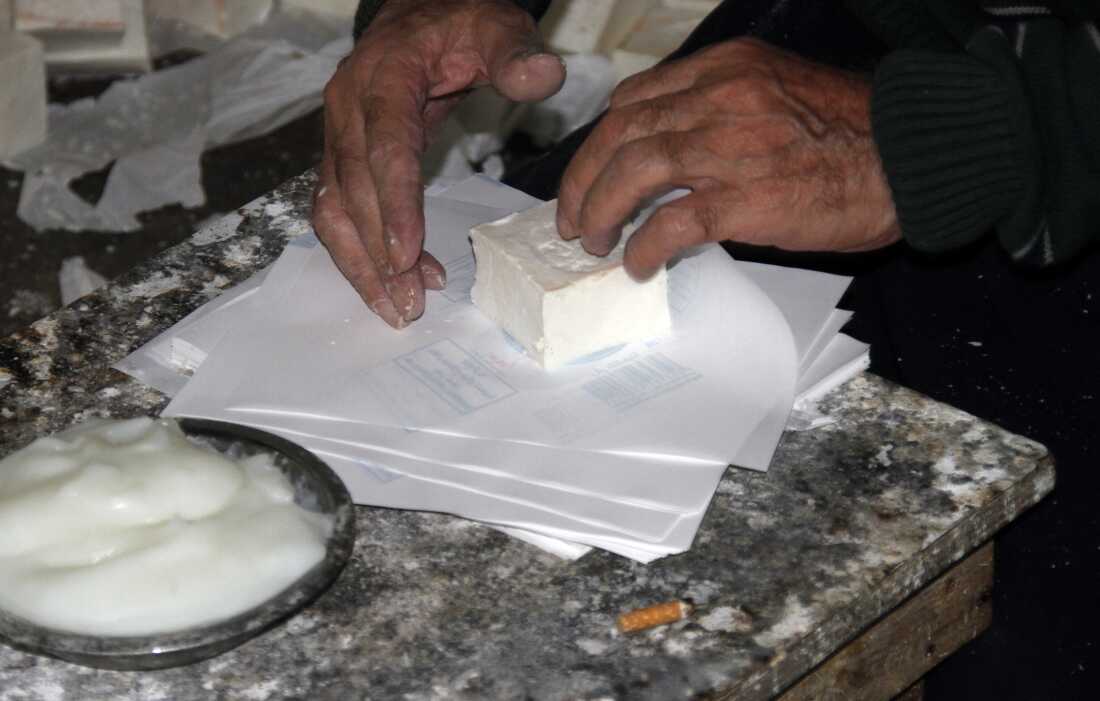

A worker wraps a soap bar by hand in the company’s signature white paper packaging.

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

The day before NPR visited, the Israeli military raided the old city of Nablus, for what it said was counterterrorism purposes, shooting several people. The factory kept operating, but it’s disruptive and dangerous, says Qubbaj.

So, he adds, getting recognized by the U.N. cultural agency at a difficult time like this makes it all the more special. While UNESCO’s well-known World Heritage List includes important sites around the world, its Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity category designates different cultures’ products and customs — like sake from Japan, for example.

“In view of this siege, all this political unrest, all this oppression against the Palestinian people, a UNESCO recognition of our soap brings not only pride, but it is a celebration of many years of working on this soap,” he says. “We want to keep this legacy alive.”

The top floor of the factory is a wide open room, with slick cement floor. When the consistency of the soap mixture downstairs is ready — usually after a week of boiling on and off — porters carry it up the stairs in metal buckets, one after another, spreading it on the floor to harden.

Then it’s cut into bars using long pieces of thread, and stacked in high cylindrical towers to dry for about three months.

The final step in the process can be heard from the next room, a very rhythmic flutter. Men sitting on the ground, surrounded by bars of soap, wrap each bar by hand in the company’s signature white paper packaging stamped with blue Arabic lettering and two red keys, atop small wooden tables perched in front of them. It’s mesmerizing to watch.

Floor manager Sultan Qaddura stands nearby, laughing with one of the wrappers as they work. He says that many of them can wrap around a thousand bars an hour.

“We call this soap the white gold of Nablus,” he says with a smile. Quddura has also been working at the factory for decades, as have most of the men wrapping.

He says the UNESCO recognition has made them all very, very proud. “We work so hard to preserve this history. It’s not just soap, it’s part of our identity,” he says.

Opened in 1872, Touqan is one of the oldest traditional Palestinian soap factories still in operation.

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Abed Omar Qusinis for NPR

Downstairs the soap has just started to boil, with big, heavy bubbles slowly rising to the surface.

Musa Assakhal expertly checks the consistency.

“It’s almost there,” he says.

Tomorrow, he says the porters will come and carry it upstairs. And then a new batch will be mixed, so the process can start all over again, just like it has for more than 150 years.

Nuha Musleh contributed to this report from Nablus, West Bank.