“I love emergencies,” Kerry McCauley tells The Independent. “I love the challenge. I love life-and-death situations. It gets me going. It’s just what I live for.”

And that’s useful, because Kerry performs one of the most dangerous civilian piloting jobs on the planet — flying brand-new light aircraft across oceans and continents to the buyers. These are planes that are unable to fly above storms and aren’t equipped with the sophisticated navigational aids found in jetliners. Plus, Kerry is on his own.

He explains: “If the new owner doesn’t want to be the one that’s stupid enough to fly it over the ocean, that’s when they call a ferry pilot.”

In any given year, three pilots die ferrying planes across the North Atlantic. And 63-year-old Kerry, who lives in Menomonie, Wisconsin, has known pilots duck out and hand the keys back before leaving the mainland.

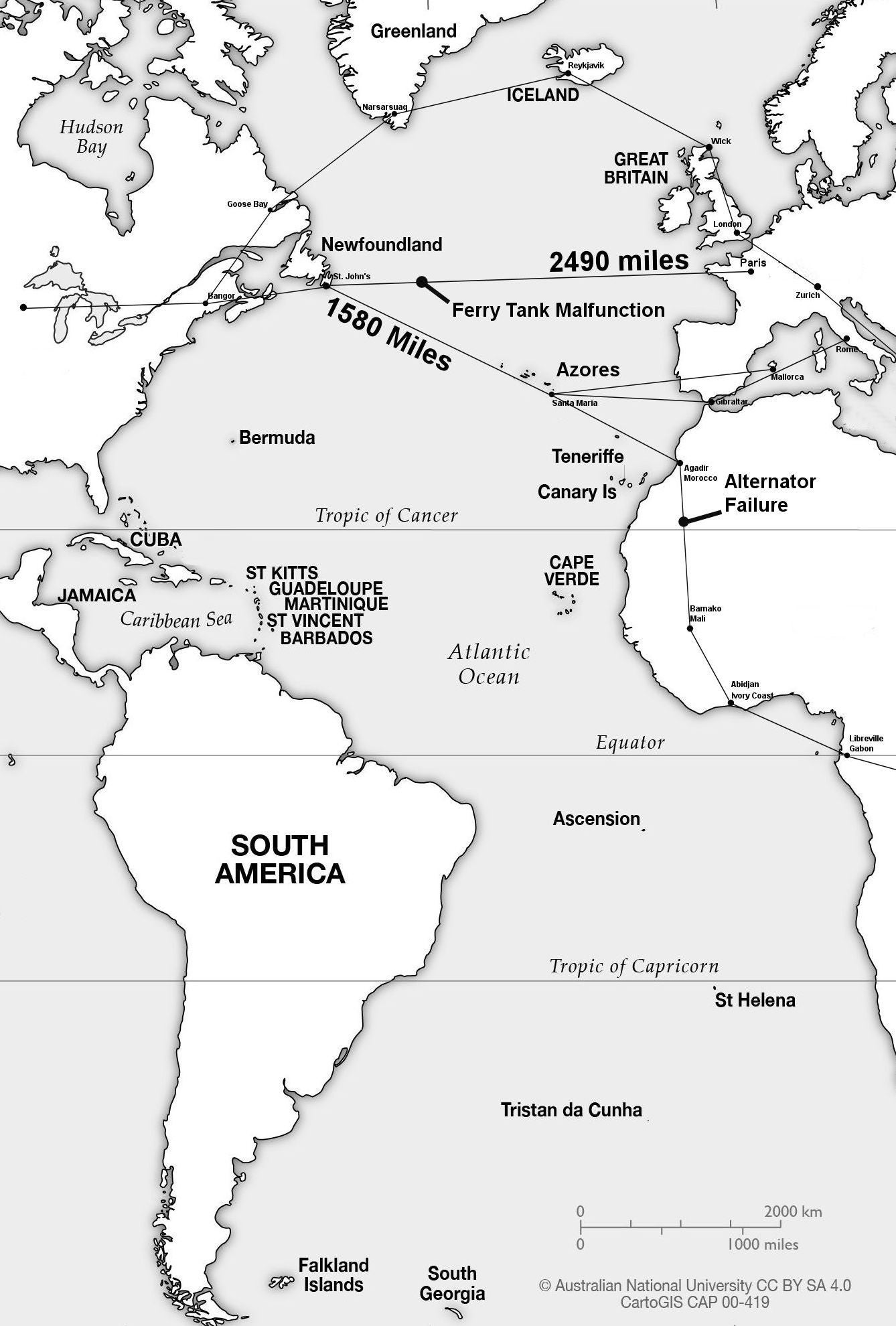

When ferrying planes from North America to Europe or Africa, to “shrink” the Atlantic, a pit stop is made at the airport that’s furthest east — St. John’s International in Newfoundland.

Kerry — who’s documented his ferry piloting daredevilry in two books, Ferry Pilot: Nine Lives Over the North Atlantic and Dangerous Flights — reveals: “There’s lots of guys, they’ll get to St John’s, which is the last stop before crossing the North Atlantic, and they look out — you can see the ocean from the airport – and realize that’s just way too much water.

“They’ll turn around and land or not even go, just put the keys in the plane, and call the customer and tell them they can’t do it, that it’s a really stupid idea.”

And many would agree that they’re right.

Flying a light propeller plane across the Atlantic is risky in the extreme for several reasons.

First of all, they can’t fly above storms like jetliners can. “Most of these small planes don’t have the performance to get up there,” remarks Kerry, who In Nine Lives over the Atlantic describes being “tossed around like a rag doll” by a storm over Africa.

At one point, his plane plunged a thousand feet in seconds.

He writes: “A strong downdraft made it feel like a trapdoor had opened beneath me. Loose items floated around the cockpit… as I tried to arrest the uncontrolled descent.”

Ferry pilots do have access to weather reports, of course, but they can’t always be relied upon and are often out of date by the time the destination is reached, with light aircraft flying at speeds of between 100 and 150mph taking many hours to travel vast distances.

And if things turn nasty, the pilot just has to deal with it.

Kerry explains: “The weather reporting thing, that’s what’s also challenging as a ferry pilot, because you’re traveling these long distances, and many hours — I’ve had legs that are up to 14-and-a-half hours long. So, before your flight, you get a weather report that’s already a couple of hours old and realize you’re going to fly for 14 hours and won’t really know what the weather’s going to be like when you arrive at your destination, because that weather report is 15 or 16 hours old.

“And as you know, weather changes all the time. I mean, they can’t get the afternoon right half the time on the forecast, so you have to be ready to deal with whatever you find.”

Navigational aids in a light aircraft are also far inferior to airliners.

Kerry reveals: “My first ferry flight was in 1990 and that was before GPS was on the scene.

“I did eight crossings with nothing but a paper map, a winds aloft forecast [for winds and temperatures] and a stopwatch, just like Charles Lindbergh [who made the first nonstop transatlantic flight from New York to Paris in 1927]. I mean very literally, no difference.

“I actually had when I started, less navigation equipment than they had in the 50s and 60s. I would just get a winds aloft forecast for the whole North Atlantic, and I would get my huge paper map out and calculate each point, what my headings were supposed to be and what the winds are going to do, and make my own call.

“And if the weather was sufficient I’d just go for it and trust that my calculations were correct.

“And the problem with that? The winds aloft forecast is just that, a forecast. If that forecast is wrong, you can be blown hundreds of miles off course, or run into a headwind you didn’t anticipate. And the problem with that is, with no navigation equipment, I don’t know that I’m in trouble until I’m way deep into trouble.”

Does GPS lower the risk? Not according to Kerry.

He explains: “When GPS started, more pilots got killed crossing the North Atlantic because that scary part of the navigation was taken out of it. Now, all these pilots who wouldn’t dare do it in the past think they can’t get lost and become suddenly brave enough to cross the Atlantic.

“But that’s not the only part of ferry flying. You have to be a weather expert. You have to be a maintenance expert. You have to know your plane.”

And that plane has propeller engines, far less reliable than jet engines on an airliner that Kerry remarks would be “maintained by a big field of technicians”.

Light aircraft “just aren’t designed for long-distance travel”.

And once you’re mid-Atlantic, there is very little chance of a rapid rescue.

Kerry reveals: “Once you’re beyond about 150 to 200 miles, you’re beyond the reach of helicopters. So, if you happen to go into the water, you can’t be rescued by anything other than a boat.

“They can send a big search-and-rescue plane to go see you and maybe drop you a nicer raft than the one you’re in. But if you go down 400 miles out into the ocean, you’re waiting on a ship, and ships are slow. You might be in the water for 24 to 48 hours or more.

“And the North Atlantic is very cold. Even if you’re in a survival suit, in a raft, 48 hours is a long time to be sitting in cold water.”

Kerry, who runs a skydiving school, reveals that he’s made over 100 ferry pilot trips, despite all the risks and numerous close calls, the most hair-raising of which was when he had a fuel emergency mid-Atlantic, while following Lindbergh’s 1927 flight path.

He was flying a 1994 single-engine Beechcraft Bonanza to Paris, a “butt-numbing” 2,487 miles from St John’s, when his fuel ran low and the reserve tanks in the cabin behind him failed.

The pilot recalls: “I was about four hours into the flight, past the point of no return, and I switched over to my ferry tanks — big metal fuel tanks to give the plane the range to cross the ocean. But the ferry tank wasn’t working. There’s no way I was going to make it back. And this is the middle of the night. I was at 15,000 feet with no one to help me.

Read more: Worried about turbulence? The hack for discovering how bumpy your next flight will be

“We almost always fly alone. We don’t have a co-pilot most of the time, just because it’s too expensive to bring somebody else along.

“I had to find a way to fix it, or I was going to die. I had a raft, but I was under no illusions about surviving. I was literally in the middle of the North Atlantic. There was no way someone was going to come and get me.”

Kerry realized that the pressurization system for the tanks was broken — the fuel wasn’t being pushed through to the wing tanks.

But Kerry remained calm.

“I didn’t allow myself to panic,” continues Kerry. “I’ve had a lot of emergencies, and I’ve learned over the years to take any panic and fear and set that aside.”

It dawned on Kerry that he would need to manually pressurize the tanks to push the fuel through by blowing into a pressurization hose that was attached to them.

Kerry explains: “I thought, ‘If I can blow up an air mattress, maybe I can blow up a steel tank.’ And I just stuck that hose in my mouth and started blowing. And after a few minutes some fuel moved and I realized it worked. But I realized I was going to have to blow into that tank all night. So, I had to sit there at 15,000 feet with no oxygen, blowing into that tank for eight and a half hours with no help and gas fumes in the plane.

“I’m in high altitude, no oxygen, got super hypoxic, passed out three times. But there’s nothing else to do. You don’t have a choice. You have to dig inside yourself and find a way to find a way to survive.”

The elephant in the room for some reading all this might be the question of why light aircraft aren’t just shipped to their customers.

Kerry reveals that taking a plane apart and putting it back together again is not a sensible plan.

Read more: Fascinating photos reveal Delta’s flight attendant uniforms through the decades

He explains: “It is possible to take the wings off an airplane and ship it in a container, but that usually doesn’t work out very well. It’s a lot more expensive. There’s a lot of maintenance involved. And airplanes aren’t designed to have the wings come off and back on again.

“A lot of times, parts get lost when they put the wings on. Sometimes, it never just flies quite right again. A lot of times you’re going to a destination where they don’t have the maintenance facilities for that. Plus, it could get damaged.

“So, the vast majority of the time a plane needs to be shipped overseas, it’s flown by a ferry pilot.”

Kerry explains that his full-time job at the moment is running his skydiving school, but he will still occasionally make a ferry pilot run.

He says: “I’m a lot pickier on what I’ll do these days, because I don’t need to prove anything anymore.

“I’ve done it over 100 times, and I’ve risked my life far too many times. But I’ll still take a trip if it’s a grand adventure, and if it’s a cool airplane I want to fly, or it involves a cool destination.

“Plus, I just can’t seem to stop it. I’m good at it. It’s kind of what I was born for.”

For more from Kerry, visit his website – kerrymccauley.com.