Controlled fires in laboratory safety simulations help lab workers to learn how to respond effectively to lab emergencies.Credit: JohnAlexandr/iStock/Getty

In August 2016, Margaret Braasch-Turi began her graduate studies in the department of chemistry at Colorado State University (CSU) in Fort Collins. During orientation week, when she was getting familiarized with the laboratory-safety protocols, she couldn’t tell right away that something was wrong as she entered one of the labs, even though a very strong smell of almonds lingered in the air. Then she saw the pool of bodies lying on the floor at the end of the room. A few seconds later, she too was dead.

At least, that’s how it would have seemed to a casual observer. Braasch-Turi and the rest of the group had been participating in a simulated lab-accident drill. They were a little shocked when the instructors overseeing the exercise tapped them on the shoulder and told them their fate. “What do you mean, we’re dead?” she recalls thinking. “What did we miss?” It turned out to be a simulated leak of cyanide, which smells similar to almonds.

From crevasse falls to polar bears, train fieldwork leaders for emergencies

It’s a dangerous situation that anyone working in a research lab might face, yet few researchers are trained to catch the warning signs and respond appropriately. With this in mind, Ben Reynolds, a lab coordinator at CSU’s chemistry department and one of the instructors, decided about ten years ago to take the standard laboratory safety training — based on online presentations or reading a safety manual — to a new level. He did so by recreating potential accidents, getting his students to respond to the situation and then assessing what they learnt. “I mean, how many more training modules can a grad student or an undergrad take where they’re just clicking through a PowerPoint presentation?” he asks.

Simulations of real emergencies can trigger strong emotions and unexpected issues. To prepare students, institutions worldwide are using lab-accident drills, also known as fantasy lab accidents, and other activities to make training exercises more fun, while also teaching students to manage stress and understand emergency procedures. These drills help participants to identify hazards. They also enable staff to carry out assessments of safety culture, and spark open discussions. (CSU paused its lab-accident drills during the COVID-19 pandemic to prioritize mental–health training, and has not resumed them.)

Over the course of one afternoon, Braasch-Turi and the other participants encountered electrocutions, explosions, chemical spills and other emergencies, all acted out by other students and university staff who brought out their theatrical skills to make the scenarios as realistic as possible. They shattered glass, started controlled fires, screamed with despair, writhed on the floor and leaked out pools of fake blood in front of flustered students who had to work out how to respond to the situations without getting ‘injured’ themselves.

Halloween make-up makes injuries look and feel real in fantasy lab-accident drills.Credit: Anthony Appleton

The scenarios ran from 15 to 20 minutes and students played various parts, such as taking notes, leading the response or making a 911 emergency call to Reynolds’ answering machine. Each exercise ended with a debriefing to run through what had gone right or wrong. Then they moved on to the next scenario. By the end of the afternoon, everyone had experienced each role.

“Wow, this is really stressful. I don’t like this,” Braasch-Turi recalls thinking. As a new PhD student, she felt unprepared to be the person in charge of an accident scene as a lab member or teaching assistant. However, her perspective shifted after the training. Not only had it been more fun than a typical training session, but she also felt more confident and prepared to face an emergency in a range of lab settings. “It helped us be aware of what sort of hazards could exist,” in any lab, she says.

Ready for anything

Numerous factors can lead to a lab accident. A study published in Nature Chemistry (A. D. Ménard and J. F. Trant Nature Chem. 12, 17–25; 2020) highlighted reasons including a lack of proper safety training and protective gear, researchers working alone and incorrect storage of equipment. Yet few accurate accounts of these incidents exist globally. In the United States, for example, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) establishes and enforces safety standards and healthy working conditions at workplaces, but it doesn’t track the annual incidence of lab accidents.

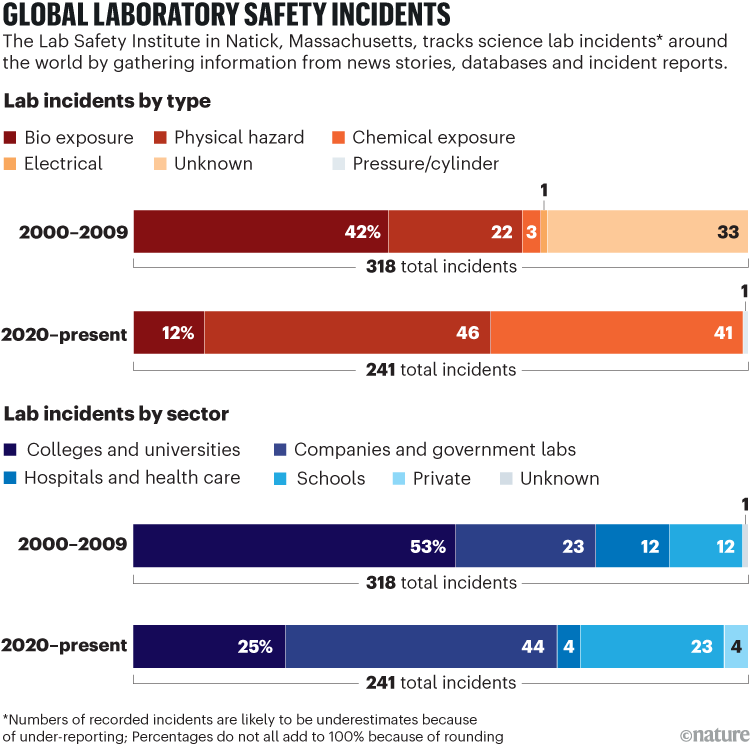

To address these gaps, the Laboratory Safety Institute, a non-profit organization that provides lab-safety education from its headquarters in Natik, Massachusetts, has been mapping lab incidents around the world on the basis of newspaper reports or public-database contents. Its founder, James Kaufman, was inspired to start the institute in 1978, after witnessing the aftermath of a lab explosion at his PhD alma mater, the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts. So far, for the 2020s, the institute has recorded about 240 accidents, ranging from chemical and biological exposures to fires and explosions, the latter being the most common (See ‘Global laboratory safety incidents’). However, its executive director, Stephen Taylor, says that the numbers recorded are likely to be lower than the actual figures, owing to under–reporting. “There’s so much to uncover in the behaviours of scientists, and things that we might be doing that cause problems.”

Source: Laboratory Safety Institute

Furthermore, OSHA regulations vary from laboratory to laboratory depending on which state they are located in, says Anthony Appleton, former safety-culture coordinator at CSU, who is now retired but consults on research safety.

Appleton says that although lab safety culture has improved since he was a student in the mid-2000s, fear of making mistakes or reporting accidents can still run deep. As a PhD student at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta in 2008, Appleton accidentally stabbed himself with a glass pipette. It was through sheer luck that he reported the injury to a trusted department administrator who knew the proper procedures. That moment motivated Appleton to dedicate his career to improving lab safety. As a safety coordinator across several institutions, he often found that principal investigators were reluctant to engage with environmental health and safety (EHS) offices.

Appleton says that one of the best things about the fantasy lab-accident programme is that it brings together researchers, lab managers, human–resource officers, principal investigators, administrators and EHS staff to have a conversation that says: “Look, we’re all here to help support research, and we can only do our job well if we are all well informed.”

Behind the scenes in the biosafety office

These drills can also help students to anticipate problems. For example, on several occasions, Reynolds’ students were unable to call 911 because the lab was underground and they had no mobile-phone signal. This prompted conversations about what to do instead, such as how to get to the nearest land line.

Institutions must also consider people with disabilities when planning lab-safety measures. Yael Medley, a chemistry PhD student at Florida State University in Tampa, has a visual impairment, which means that safety is constantly on her mind. She used to work on a lab on the seventh floor, and although she had enough vision to find her way out of the building in an emergency, she realized that other people with less vision, or with other physical disabilities, wouldn’t be that lucky. “They can’t go down the stairs or take the elevator during a fire situation, so they basically have to wait for somebody to come get them,” she says.

Medley, who once broke her leg falling down a carpeted stairwell that wasn’t clearly marked, thinks it’s important that office staff responsible for planning safety protocols include in their conversations people with disabilities, so as to properly address their needs.

The issue of disability sometimes surfaced during the fantasy lab drills at CSU, and is another reason why Reynolds thinks administrators should take part in the drills. “It makes their eyes much more wide open when you hear somebody else tell their story from their perspective,” he says.